Not far from the town of Vila Nova de Foz Côa the Museu do Côa (Côa Museum) is one of those modernist, monolithic buildings which architects swoon over in their lofty glass and steel city studios. The rest of us, stand there on a hillside, overlooking the spectacular confluence of the rivers Côa and Douro in Portugal’s Beira Alta, drinking in the marvels of nature which are spread before and beneath us. Really? I asked myself. Did they put this here?

On the outside, the museum is an austere lego-kit of concrete, textured to appear as if it exists in harmony with the granite and schist landscape at its feet. The entrance to the interior is via a long, descending ramp of the same material, set in a narrow ‘canyon’ as if the visitor were entering the bowels of the earth itself – representing a seismic fault line which exists nearby, I was informed. The jury of my aesthetics is still out, and I have a feeling that its deliberations may be long and hard before a verdict on the building’s design is returned. However, once inside and in the capable hands of Antonio Batarda, the museums hugely knowledgeable coordinator of educational services, my architectural leanings are quickly forgotten. You see, I have something bordering on a passion for rock and cave art, and that is what the Museu do Côa is all about.

On the outside, the museum is an austere lego-kit of concrete, textured to appear as if it exists in harmony with the granite and schist landscape at its feet. The entrance to the interior is via a long, descending ramp of the same material, set in a narrow ‘canyon’ as if the visitor were entering the bowels of the earth itself – representing a seismic fault line which exists nearby, I was informed. The jury of my aesthetics is still out, and I have a feeling that its deliberations may be long and hard before a verdict on the building’s design is returned. However, once inside and in the capable hands of Antonio Batarda, the museums hugely knowledgeable coordinator of educational services, my architectural leanings are quickly forgotten. You see, I have something bordering on a passion for rock and cave art, and that is what the Museu do Côa is all about.

Down below where we stand, on the banks of the Côa River, Antonio explains, is one of the greatest collections of Upper Palaeolithic rock art (up to 30,000 years old) to be found anywhere in the world – and they were almost lost forever. Back in the late 1980’s, as planning for the construction of a dam which would submerge the entire valley was underway, the first examples of the ancient rock carvings was discovered. Over the coming years more and more individual pieces, mostly depicting the creatures typical of the age; horses, goats, aurochs (wild cattle), deer and fish, were discovered over an ever-increasing number of sites. It was becoming clear that this was a find of worldwide, human importance.

Down below where we stand, on the banks of the Côa River, Antonio explains, is one of the greatest collections of Upper Palaeolithic rock art (up to 30,000 years old) to be found anywhere in the world – and they were almost lost forever. Back in the late 1980’s, as planning for the construction of a dam which would submerge the entire valley was underway, the first examples of the ancient rock carvings was discovered. Over the coming years more and more individual pieces, mostly depicting the creatures typical of the age; horses, goats, aurochs (wild cattle), deer and fish, were discovered over an ever-increasing number of sites. It was becoming clear that this was a find of worldwide, human importance.

Over the following years academics, politicians and the local population campaigned to have the dam’s construction stopped and the site preserved, using the imaginative slogan, ‘As gravuras não sabem nadar’, Petroglyphs can’t swim. With a change in the country’s government in 1995 the construction plans were shelved and the carvings were saved, the entire site along the banks of the Côa River eventually, in 1997, being afforded the status of a UNESCO world heritage site.

Over the following years academics, politicians and the local population campaigned to have the dam’s construction stopped and the site preserved, using the imaginative slogan, ‘As gravuras não sabem nadar’, Petroglyphs can’t swim. With a change in the country’s government in 1995 the construction plans were shelved and the carvings were saved, the entire site along the banks of the Côa River eventually, in 1997, being afforded the status of a UNESCO world heritage site.

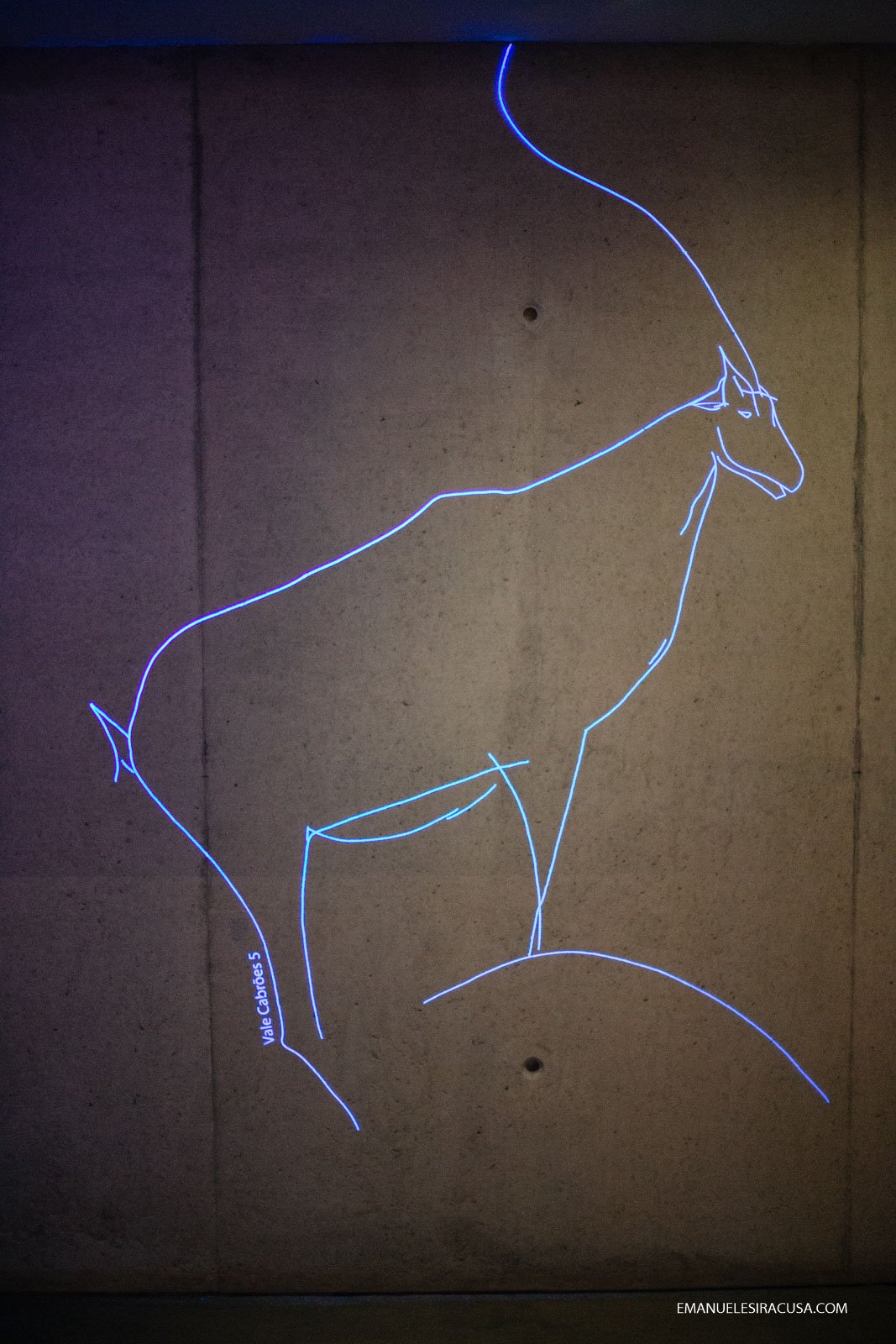

The museum, through an impressive display of models, replicas and dioramas, goes a long way to explaining the origins of the rock art, and speculatively delves into the reasons for their existence here in this spot, and into the lives of those who created them. Throughout the museum life-sized and super enlarged examples of the art are replicated on the walls of their modern day spaces, for those who may not get to witness them up close and personal. The many thousand individual pieces of rock art of the Côa Valley are unlike their counterparts found in nearby Spain and France – whose existence were discovered mainly in caves used by the continent’s earliest inhabitants – the rock art of the Côa Valley have all been created in the open air, on the walls of the cliffs adjoining the river’s fertile flood plains and within earshot of its gurgling waters.

The museum, through an impressive display of models, replicas and dioramas, goes a long way to explaining the origins of the rock art, and speculatively delves into the reasons for their existence here in this spot, and into the lives of those who created them. Throughout the museum life-sized and super enlarged examples of the art are replicated on the walls of their modern day spaces, for those who may not get to witness them up close and personal. The many thousand individual pieces of rock art of the Côa Valley are unlike their counterparts found in nearby Spain and France – whose existence were discovered mainly in caves used by the continent’s earliest inhabitants – the rock art of the Côa Valley have all been created in the open air, on the walls of the cliffs adjoining the river’s fertile flood plains and within earshot of its gurgling waters.

After plans to shelve the construction were in place work on the museum began in earnest, finally opening its doors to the public in 2010. Alongside the museum, the whole area around the Côa Valley was designated as a Park Arquelógico (Archaeological Park) which now attracts an ever-growing number of visitors (41,000 in 2015) who come to witness the work of our ancestors, enjoy the many walking routes through the area, boat and cycling tours, and the spectacular, guided night tours – the best way by far to fully appreciate the rock art is at night with the aid of a guide’s illuminating torch and knowledge.

After plans to shelve the construction were in place work on the museum began in earnest, finally opening its doors to the public in 2010. Alongside the museum, the whole area around the Côa Valley was designated as a Park Arquelógico (Archaeological Park) which now attracts an ever-growing number of visitors (41,000 in 2015) who come to witness the work of our ancestors, enjoy the many walking routes through the area, boat and cycling tours, and the spectacular, guided night tours – the best way by far to fully appreciate the rock art is at night with the aid of a guide’s illuminating torch and knowledge.

However, as Antonio explained, “The real museum is not here, the real museum is the last 17km of the Côa Valley”. Pointing at the replicated engraving of a lady in traditional Portuguese dress standing next to a steam train, Antonio points out, “It was not just the Palaeolithic period which gave us the rock art, but it has been added to throughout the different epochs over the millennia, generation after generation, right up to the 20th century.

However, as Antonio explained, “The real museum is not here, the real museum is the last 17km of the Côa Valley”. Pointing at the replicated engraving of a lady in traditional Portuguese dress standing next to a steam train, Antonio points out, “It was not just the Palaeolithic period which gave us the rock art, but it has been added to throughout the different epochs over the millennia, generation after generation, right up to the 20th century.

There is no definitive reason why the area has produced such a multitude of finds; there are theories, that is all. Some argue over their religious significance, others espouse the theory of the arts sympathetic magic, fertility rites and shamanism, then there are the theories of structuralism and post-structuralism, and my own personal favourite (and that of Pablo Picasso), the theory of art for art’s sake. We will never the exact reasons why our ancestors spent their days and nights with primitive tools in hand, carving in stone a graphic account of the world which they saw around them and in which they lived. But because of their perseverance, and the combined will of the many, they are here to stay and will never be forgotten.

There is no definitive reason why the area has produced such a multitude of finds; there are theories, that is all. Some argue over their religious significance, others espouse the theory of the arts sympathetic magic, fertility rites and shamanism, then there are the theories of structuralism and post-structuralism, and my own personal favourite (and that of Pablo Picasso), the theory of art for art’s sake. We will never the exact reasons why our ancestors spent their days and nights with primitive tools in hand, carving in stone a graphic account of the world which they saw around them and in which they lived. But because of their perseverance, and the combined will of the many, they are here to stay and will never be forgotten.

Rock Art UNESCO Heritage of the Côa Valley

Perhaps I had been wrong, perhaps the architects knew what they were doing all along. From the opposite side of the Côa River, the Museu do Côa, which I had at first thought to be a blot on the canvas of an immaculately wild landscape, appeared to find its place nestled among the bare rock and shrub of the hilltop overlooking the river valley. I silently made my apologies. Leaving the tiny and silent village of Castelo Melhor the jeep descended downwards along a rough and winding track towards the Côa river. Here it was wild, and in the last drains of evening sunlight, I began to imagine seeing the rugged landscape as our ancestors must have seen it.

Amongst the undergrowth lining the route I imagined a herd of long-horned aurochs (wild cattle now extinct) silently watching as we passed. In the hills behind us, there would be wild goats and herds of free-roaming horses. And on the banks of the river below, I could picture the first lights of the ancestor’s fires as the sun set behind the mountain. It was dark by the riverbank when the jeep arrived. The sky ablaze with stars and a finger-nail of a crescent moon. I could hear the sound of the rushing waters of the Côa River and as my eyes adjusted to the Portuguese darkness, bats made their presence known, flitting between the riverside trees. A squadron of flying insects filled the beam of the guide’s torch as we made our way in silence towards the journey’s ultimate reward.

Amongst the undergrowth lining the route I imagined a herd of long-horned aurochs (wild cattle now extinct) silently watching as we passed. In the hills behind us, there would be wild goats and herds of free-roaming horses. And on the banks of the river below, I could picture the first lights of the ancestor’s fires as the sun set behind the mountain. It was dark by the riverbank when the jeep arrived. The sky ablaze with stars and a finger-nail of a crescent moon. I could hear the sound of the rushing waters of the Côa River and as my eyes adjusted to the Portuguese darkness, bats made their presence known, flitting between the riverside trees. A squadron of flying insects filled the beam of the guide’s torch as we made our way in silence towards the journey’s ultimate reward.

Ana Berlina, my guide, indicated we climb a short series of steps towards a flat rock face, her light guiding my faltering footsteps. “We’re here,” she said, almost reverently, and hunkered to her knees. At first I could see nothing but the bare flat stone illuminated in yellow light. She moved her torch low towards the ground and shone its beam directly upwards on the rock’s flat surface. Suddenly, the centuries faded away into the darkness and the Palaeolithic world reimagined itself magically in front of me. Before my eyes, the image of an aurochs took shape, his head thrown forward, his long horns swept back and his sturdy hoofless feet anchored in rock. I was silent, who made this? I thought. What hands had chipped flake by tiny flake from the stubborn granite, to reveal a sight formed in the memory and replicated here in the finest artistic detail?

Ana Berlina, my guide, indicated we climb a short series of steps towards a flat rock face, her light guiding my faltering footsteps. “We’re here,” she said, almost reverently, and hunkered to her knees. At first I could see nothing but the bare flat stone illuminated in yellow light. She moved her torch low towards the ground and shone its beam directly upwards on the rock’s flat surface. Suddenly, the centuries faded away into the darkness and the Palaeolithic world reimagined itself magically in front of me. Before my eyes, the image of an aurochs took shape, his head thrown forward, his long horns swept back and his sturdy hoofless feet anchored in rock. I was silent, who made this? I thought. What hands had chipped flake by tiny flake from the stubborn granite, to reveal a sight formed in the memory and replicated here in the finest artistic detail?

Ana moved her torch a little in another direction. One, then another, and another animalistic form revealed themselves. This time, the subject were horses, overlapping, intertwined, a muddle of shapes and lines, but one by one they too revealed themselves. One carving was a horse which appeared to have two heads; one facing forward, the other to the rear. “Perhaps they were trying to depict movement,” she said, tracing the artistic outlines with a stem of grass, careful to avoid contact with the ancient’s handiwork. We moved fifty metres downstream to another site, my mind still swimming with the concept of these unknown ‘primitives’, recording their life, chip by chip, but to what end?

Ana moved her torch a little in another direction. One, then another, and another animalistic form revealed themselves. This time, the subject were horses, overlapping, intertwined, a muddle of shapes and lines, but one by one they too revealed themselves. One carving was a horse which appeared to have two heads; one facing forward, the other to the rear. “Perhaps they were trying to depict movement,” she said, tracing the artistic outlines with a stem of grass, careful to avoid contact with the ancient’s handiwork. We moved fifty metres downstream to another site, my mind still swimming with the concept of these unknown ‘primitives’, recording their life, chip by chip, but to what end?

At the next site, it was the same. Herds of goats, cattle and horses swarmed the rock face. Is this what life was like down here on the banks of the Côa River 30,000 years ago, a veritable garden of Eden? Is this what brought the people here, the ample supplies of food which abounded on land, in the air and the water. Near the ground Ana indicated the unmistakeable outline of a salmon, even its tiny, bud-like pectoral fin included to ensure that it was indeed a salmon, it could be nothing else. Inside the deep caves of Alta Mira, Tito Bustillo and La Pasiego in Spain’s far north, I had witnessed the painted images of bulls and horses, handprints and unknown symbolic shapes, but here there was no colour. Perhaps it had faded over time, perhaps there never was colour; the shapes and outlines created with only the artist’s knowledge of their existence. Perhaps that was enough?

At the next site, it was the same. Herds of goats, cattle and horses swarmed the rock face. Is this what life was like down here on the banks of the Côa River 30,000 years ago, a veritable garden of Eden? Is this what brought the people here, the ample supplies of food which abounded on land, in the air and the water. Near the ground Ana indicated the unmistakeable outline of a salmon, even its tiny, bud-like pectoral fin included to ensure that it was indeed a salmon, it could be nothing else. Inside the deep caves of Alta Mira, Tito Bustillo and La Pasiego in Spain’s far north, I had witnessed the painted images of bulls and horses, handprints and unknown symbolic shapes, but here there was no colour. Perhaps it had faded over time, perhaps there never was colour; the shapes and outlines created with only the artist’s knowledge of their existence. Perhaps that was enough?

It is this lack of certainty which conjures the magic of this place. The questions summersault in your mind long after you have left the Côa River valley. Is that what they wanted when they created their art? That magic of defining a living thing in a surface as stubborn and lasting as the very rocks on which they live? I don’t know the answers. Nobody does, but it’s the speculation and the questions which will leave us intrigued, especially now, in a world where the answers to so much are but a click away. It is these questions and this unknowing that will have visitors returning to this place of magical beauty for as long as the ‘words’ of our ancestors remain living in stone, here by the waters of the Côa River.

It is this lack of certainty which conjures the magic of this place. The questions summersault in your mind long after you have left the Côa River valley. Is that what they wanted when they created their art? That magic of defining a living thing in a surface as stubborn and lasting as the very rocks on which they live? I don’t know the answers. Nobody does, but it’s the speculation and the questions which will leave us intrigued, especially now, in a world where the answers to so much are but a click away. It is these questions and this unknowing that will have visitors returning to this place of magical beauty for as long as the ‘words’ of our ancestors remain living in stone, here by the waters of the Côa River.

Faia Brava Natural Reserve

The term ‘rewilding’ is defined in the dictionary as the following: ‘restore (an area of land) to its natural uncultivated state (used especially with reference to the reintroduction of species of wild animal that have been driven out or exterminated). At the Faia Brava privately managed Reserve, in Centro de Portugal’s Beira Alta region, this rewilding has become a reality. On a huge tract of land adjacent to the waters of the Côa River, its floodplains and high craggy cliffs and after only twelve years in operation, a walk through the forests, plains, mountains and meadows brings you closer to ‘wild’ nature than you ever imagined in this part of modern Europe.

Operated and managed by a group called ATN (Associação Transumância e Natureza), the reserve is an area of several hundred hectares which has been allowed and encouraged to return to a state of wildness, unseen since before the presence of mankind in the area. It is an ambitious project, to say the least, a project without a timetable. As the Faia Brava’s field biologist Eduardo Realinho states, “there is no timetable, nature doesn’t allow for that.” Since 2011 Faia Brava has been part of the ‘Rewilding Europe’ imitative, an organisation devoted to preserving the last truly wild places across Europe and reintroducing species of large mammals which have been lost to human encroachment or hunting.

Operated and managed by a group called ATN (Associação Transumância e Natureza), the reserve is an area of several hundred hectares which has been allowed and encouraged to return to a state of wildness, unseen since before the presence of mankind in the area. It is an ambitious project, to say the least, a project without a timetable. As the Faia Brava’s field biologist Eduardo Realinho states, “there is no timetable, nature doesn’t allow for that.” Since 2011 Faia Brava has been part of the ‘Rewilding Europe’ imitative, an organisation devoted to preserving the last truly wild places across Europe and reintroducing species of large mammals which have been lost to human encroachment or hunting.

Already on the reserve herds of wild cattle and horses (the first truly wild foals have been born on the reserve in recent times) can be witnessed grazing the unkempt countryside. Small mammals such as rabbits have returned to the area, and with the return of the rabbit the skies are full of raptors, such as eagles, kites and falcons, while the ledges of the riverside cliffs are home to large breeding flocks of vultures; Griffon, Egyptian and Black.

Already on the reserve herds of wild cattle and horses (the first truly wild foals have been born on the reserve in recent times) can be witnessed grazing the unkempt countryside. Small mammals such as rabbits have returned to the area, and with the return of the rabbit the skies are full of raptors, such as eagles, kites and falcons, while the ledges of the riverside cliffs are home to large breeding flocks of vultures; Griffon, Egyptian and Black.

In the meadows butterflies, flit among the wildflower blooms and the song of a huge variety of birds fills the air. In fact recently, Eduardo is proud to point out that one species of butterfly (Mazarine Blue), long thought to be critically endangered has once again been recorded within the reserve. But the road to this rewilding hasn’t been easy. There have been many obstacles along the way, most of them to difficulty connected to the continuous financing of the project. As Eduardo’s colleague and executive director of the project, Pedro Prato explains. “The bureaucracy is sometimes a nightmare. We have the same status as the local farmers, but with the same subsidies being applied to us. We are actively attempting to make space for nature, as was outlined by law back in 2010, but it hasn’t been easy.”

In the meadows butterflies, flit among the wildflower blooms and the song of a huge variety of birds fills the air. In fact recently, Eduardo is proud to point out that one species of butterfly (Mazarine Blue), long thought to be critically endangered has once again been recorded within the reserve. But the road to this rewilding hasn’t been easy. There have been many obstacles along the way, most of them to difficulty connected to the continuous financing of the project. As Eduardo’s colleague and executive director of the project, Pedro Prato explains. “The bureaucracy is sometimes a nightmare. We have the same status as the local farmers, but with the same subsidies being applied to us. We are actively attempting to make space for nature, as was outlined by law back in 2010, but it hasn’t been easy.”

Now with plans afoot to enlarge the reserve, ensuring greater availability of natural and wild corridors for the movement of wildlife, they are sure to encounter more bureaucracy and more challenges. “We are attempting to work with local landowners, we are trying to promote the alternative use of the land to generate a future for both farmers and the native flora and fauna. We are still in our infancy and ideas [for co-operation] are still being developed. Some of the ideas so far are the production of ancillary products from the rewilded land; wild honey farming, wild flowers and fungus gathering, non-destructive tourism opportunities, and many ideas which are sure to exist out there, but ideas which we still haven’t discovered yet. But we are sure they are there.” It seems that the negative spiral of land abandonment, loss of biodiversity and diminishing local culture has turned into new prosperity, attracting and inspiring many visitors, also from far outside the region.

Now with plans afoot to enlarge the reserve, ensuring greater availability of natural and wild corridors for the movement of wildlife, they are sure to encounter more bureaucracy and more challenges. “We are attempting to work with local landowners, we are trying to promote the alternative use of the land to generate a future for both farmers and the native flora and fauna. We are still in our infancy and ideas [for co-operation] are still being developed. Some of the ideas so far are the production of ancillary products from the rewilded land; wild honey farming, wild flowers and fungus gathering, non-destructive tourism opportunities, and many ideas which are sure to exist out there, but ideas which we still haven’t discovered yet. But we are sure they are there.” It seems that the negative spiral of land abandonment, loss of biodiversity and diminishing local culture has turned into new prosperity, attracting and inspiring many visitors, also from far outside the region.

Visitors to the area can enjoy the many kilometres of unspoilt walking trails throughout the reserve, 4WD safari tours with a licensed guide, bird watching and a range of educational courses such as the identification of wild birds and flowers. One of the highlights of Faia Brava (at least for me) is a visit to the camouflaged hide where visitors can observe the huge flocks of vultures on a feeding site. There is nothing quite like the experience of sitting quietly in the hide as the vultures circle overhead, the shadows of their unseen silhouettes spinning like a vortex on the ground outside. Until at some unspoken moment, the land en-masse to devour the bones and meat left a mere 15 metres from where you sit, camera poised. During my visit, we were immensely lucky to witness all three species of vulture which frequent the area – Griffon Vulture, Egyptian Vulture and Black Vulture, on the one ground at the one time.

Visitors to the area can enjoy the many kilometres of unspoilt walking trails throughout the reserve, 4WD safari tours with a licensed guide, bird watching and a range of educational courses such as the identification of wild birds and flowers. One of the highlights of Faia Brava (at least for me) is a visit to the camouflaged hide where visitors can observe the huge flocks of vultures on a feeding site. There is nothing quite like the experience of sitting quietly in the hide as the vultures circle overhead, the shadows of their unseen silhouettes spinning like a vortex on the ground outside. Until at some unspoken moment, the land en-masse to devour the bones and meat left a mere 15 metres from where you sit, camera poised. During my visit, we were immensely lucky to witness all three species of vulture which frequent the area – Griffon Vulture, Egyptian Vulture and Black Vulture, on the one ground at the one time.

However, as Pedro adds, “With the coming of visitors, also comes our number fear. Fire!” He sits back and thinks for a moment, “Did you know that a total combined area, the size of Portugal, burns every 15 years. 99% of those fires are created by man, our work here could be endangered, or even wiped out overnight by one careless action.” A frightening statistic, but one which they are actively trying to change through education. “Every 12 and 13-year-old schoolchild in the area spends at least two days each year on the reserve where we educate them about everything involving the wildlife of the area and the necessity to protect the environment against fires.”

However, as Pedro adds, “With the coming of visitors, also comes our number fear. Fire!” He sits back and thinks for a moment, “Did you know that a total combined area, the size of Portugal, burns every 15 years. 99% of those fires are created by man, our work here could be endangered, or even wiped out overnight by one careless action.” A frightening statistic, but one which they are actively trying to change through education. “Every 12 and 13-year-old schoolchild in the area spends at least two days each year on the reserve where we educate them about everything involving the wildlife of the area and the necessity to protect the environment against fires.”

Despite the obstacles they face both men are excited and remain infectiously positive about the future of Faia Brava, its wildlife, and the wellbeing of the local community here along the banks of the beautiful Côa River.

Despite the obstacles they face both men are excited and remain infectiously positive about the future of Faia Brava, its wildlife, and the wellbeing of the local community here along the banks of the beautiful Côa River.

Star Camp – Sleeping under the stars

Another attraction to Faia Brava is the introduction of Star Camp. In three luxuriously appointed, environmentally sensitive, safari-like tents, visitors can experience a night in the wild, sleeping under a sky filled with stars without the intrusion of urban light pollution. You will wake to the sound of birdsong, the buzz of bees in the flower-scattered meadows, and if you’re lucky the sight of a sky full of rare birds of prey. What better way to enjoy your morning coffee.

The ‘tents’ named, ‘Aquila’, ‘Equuleus’ and ‘Taurus’ come with comfortable double beds, mosquito netting, solar-powered light and a chemical toilet. There is also an outdoor dining area which affords views of majestic sunsets over the gorge of the Côa River Valley. Due to the fact that there are only three ‘tents’, no road traffic and is totally isolated from the nearest urban settlement, you can be assured of a night spent in pure and natural wild tranquillity.

The ‘tents’ named, ‘Aquila’, ‘Equuleus’ and ‘Taurus’ come with comfortable double beds, mosquito netting, solar-powered light and a chemical toilet. There is also an outdoor dining area which affords views of majestic sunsets over the gorge of the Côa River Valley. Due to the fact that there are only three ‘tents’, no road traffic and is totally isolated from the nearest urban settlement, you can be assured of a night spent in pure and natural wild tranquillity.

Dão Ecopista (Dão Bicycle Path)

Dão Ecopista (Dão Bicycle Path)

With so much nature at your fingertips in Centro de Portugal’s Beira Alta, more and more visitors to the area are opting to get out and explore. One such method of doing this is along the Dão Ecopista (www.ecopista-portugal.com); an enchanting cycle path which makes use of the 49km route of a long abandoned railway line. The Ecopista runs from the quaint village of Santa Comba Dão through a flat and leafy landscape, which at times crosses the wide expanse of the Dão River, through abandoned train stations and tiny villages once fed by the rail line.

The Ecopista is suitable for cyclists of all ability due to its flat nature and allows lots of time and places for riverside picnics, visits to nearby villages and pure relaxation among some of the regions luscious greenery. Bicycles are available to hire locally, and a variety of accommodation options are available for those who wish to complete the route at their own slower pace; taking the time to enjoy the scenery, the local wines and the gastronomy of this massively bountiful region.

The Ecopista is suitable for cyclists of all ability due to its flat nature and allows lots of time and places for riverside picnics, visits to nearby villages and pure relaxation among some of the regions luscious greenery. Bicycles are available to hire locally, and a variety of accommodation options are available for those who wish to complete the route at their own slower pace; taking the time to enjoy the scenery, the local wines and the gastronomy of this massively bountiful region.

This Côa Valley in Centro de Portugal post is a part of a series of 7 posts I wrote based on my journey to Beira Alta in May 2016. Please find the links o the other articles bellow:

Beira Alta in Centro de Portugal

Historical Villages of Centro de Portugal

Casas do Côro in Centro de Portugal

Casa da Cisterna in Centro de Portugal

Disclaimer:

This Côa Valley in Centro de Portugal post was written by my inspiring friend Brendan Harding as part of my ongoing collaboration with the Centro de Portugal Tourism Board. All opinions are my own. Photo credits to my inspiring friend Emanuele Siracusa.

Brendan Harding

My name is Brendan Harding and I was born and raised in Ireland – that small teddy-bear-shaped island which clings to the edge of the European landmass.

6 Comments

Add comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

[…] Côa Valley in Centro de Portugal […]

[…] Côa Valley in Centro de Portugal […]

[…] Côa Valley in Centro de Portugal […]

[…] Côa Valley in Centro de Portugal […]

[…] in clean blue skies, and wide deep-bodied rivers offer nourishment to the wines of the Dão and Côa valleys. It is a land of kings and knights, Templars and Moors, a land of historic villages and castles […]

[…] Côa Valley in Centro de Portugal […]